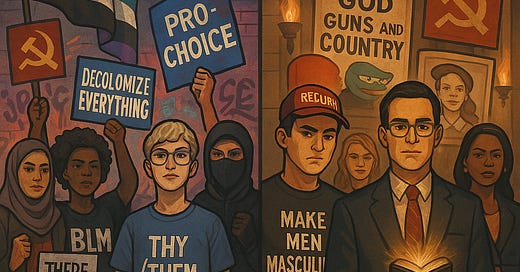

The Woke Liturgy: Ritual, Belief, and the Return of the Sacred

Inheriting Ritual Without Reverence

Friedrich Nietzsche’s declaration that “God is dead” is often misread as a triumph of secular liberation. In truth, it is a statement of crisis. Nietzsche was not celebrating the decline of traditional religious belief, but warning of the metaphysical consequences that would follow. The death of God, for Nietzsche, did not mean the disappearance of religion’s psychological, symbolic, or ethical functions. It marked the loss of a shared transcendent framework — a structure of meaning that had anchored Western civilization for centuries. In its absence, he foresaw not rational enlightenment, but a resurgence of belief in displaced forms.

I’ll admit, while I live within the West, I am not fully of it. Judaism has undeniably shaped Western thought, alongside Greek philosophy, Roman structure, and (Judeo-) Christian theology, but the concerns raised here do not fully map onto the Jewish experience. The divergence began when the Roman Empire adopted Christianity as its official religion. From that moment on, religion in the West became something that could be added to a people or a state — an institutional layer, detachable when no longer convenient.

In Judaism, no such detachment is possible. There is no Jewish people without Jewish law. The two are not parallel entities, but one continuous organism. The Latin religio, once denoting ritual obligation (see Cicero’s De Natura Deorum), was reinterpreted by Christian thinkers as something primarily inward, confessional, and institutional (see Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae). Judaism never underwent that abstraction. It is not a religion, but a civilization. Untethered from the need for statecraft, because it constitutes one in itself — an embodied culture of time, law, and peoplehood.

This is not a claim of superiority, only of difference. The Western crisis arises from a disjunction: a state and culture that no longer carry their foundational religious ethos, yet remain haunted by its moral architecture. Into that vacuum rushes what we now call “wokeism.” It is not merely politics, but a surrogate liturgy. It mimics the structure of faith while denying its metaphysics. The rituals remain. The transcendence is gone.

There is, of course, a parallel crisis within the Jewish world, but it is not this one. I digress.

Today’s cultural and political landscape confirms Nietzsche’s insight. We do not live in a secular age so much as a transposed one. Religious energy has not evaporated; it has been redirected. Political ideologies, activist movements, and digital identities have absorbed the roles once held by religious institutions. The forms persist — confession, judgment, purification, excommunication, eschatology (end times theology)— but they are no longer anchored to transcendence. They operate now through media, algorithms, and collective identity.

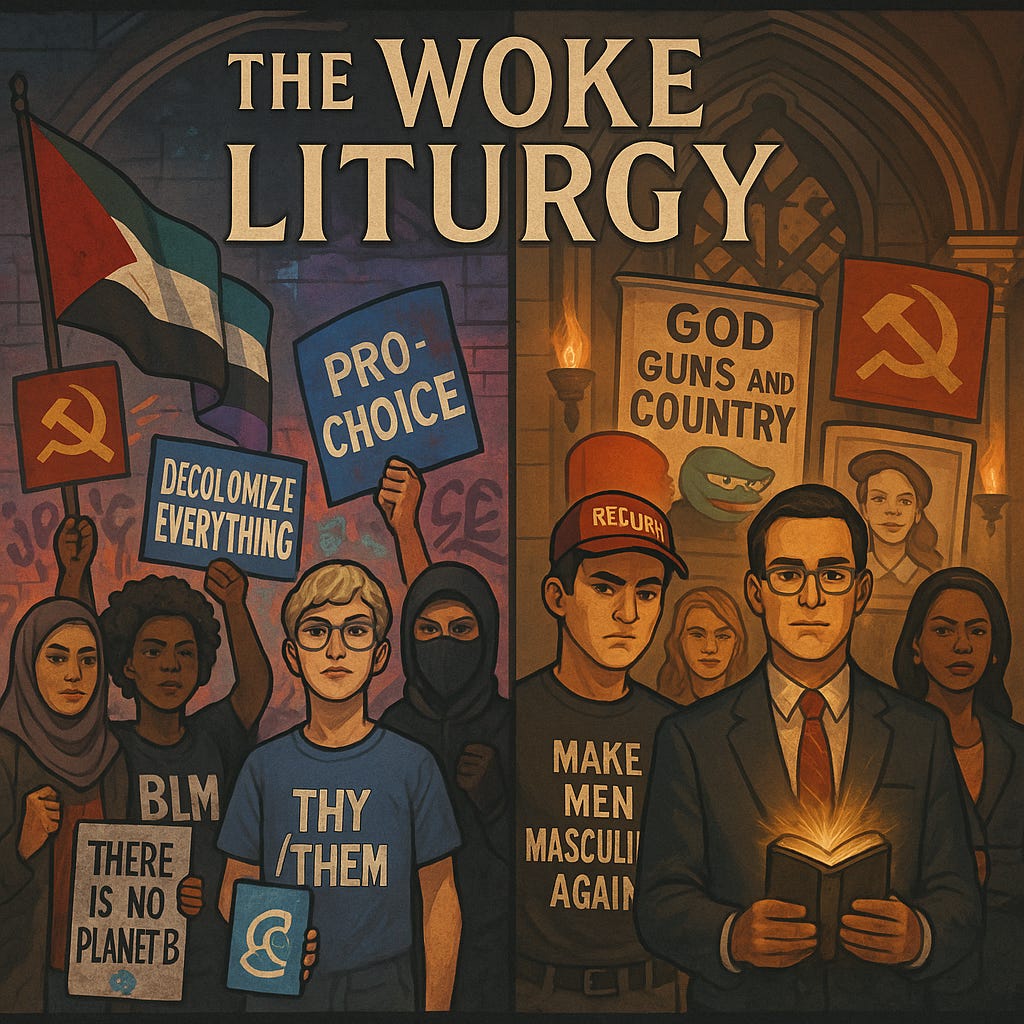

This dynamic is especially visible on the so-called woke left. Though outwardly secular and progressive, its internal logic is deeply reminiscent of the Christian moral economy it seeks to replace. Terms like privilege, allyship, and systemic oppression function analogously to sin, penance, and grace. Confession is public, usually on social media. Forgiveness is increasingly rare. Contrition must be performed, but redemption is not guaranteed. Guilt becomes a status, not a transitional state. In this moral universe, sincerity is subordinate to legibility. The imperative is not to become just, but to appear just in the eyes of the digital collective.

The rituals are not new. Only the gods have changed.

Religion and cult are deeply embedded in the human psyche. The far left and far right have not transcended belief; they have simply adopted new liturgies with old intensity.

Their holidays and pilgrimages are protests. They abstain from the “profane” days — Thanksgiving, the Fourth of July — not out of neutrality, but because those days carry the wrong mythos. Their saints are the victims of the system. Their martyrs go viral for acts of defiance against it.

Their vestments are visible: masks, pins, flags, slogans, pronouns in bios — each a badge of moral belonging. Their prophets speak into microphones, leading crowds in chants. Slogans and graffiti function as liturgy. Their scripture is algorithmic — not fixed in doctrine, but shaped by what moves the mob.

Heresy is a poorly chosen word, an unexamined bias, a joke that didn’t land. Excommunication comes through deplatforming, job loss, and public shame. The penitent may return, but only after confession: a notes app apology, a corporate statement, a thread of self-rebuke. Forgiveness is rare. The mob does not absolve. It purifies.

Their eschatology arrives through headlines and hashtags: ‘climate collapse’, ‘systemic revolution’, the ‘end of capitalism’. Their messiahs do not walk on water. They offer blueprints, policy PDFs, bureaucratic redemptions. “This time,” they promise, “it will work.”

Their zeal is intense but untethered, drifting from moment to moment. They reject myth as falsehood, not understanding that myth is how a civilization remembers itself. Nuance can bring us to actual history, but myth helps move us forward. We are not meant to live crushed by detail. We need stories that hold us together.

This logic is mirrored on the political right — what some have begun calling the “woke right.” Its reactionary and post-liberal factions also exhibit re-enchanted moralism. Though cloaked in appeals to tradition, they invoke a mythic past, warn of civilizational collapse, and dream of political restoration as eschatological deliverance. Their figures include national leaders, cultural critics, even AI systems, each imbued with messianic overtones. Their emphasis on hierarchy, purity, and order forms a rival theology, borrowing Christian form while rejecting its humility and universalism.

Both the left and right act out symbolic liturgies. Protests and riots become sacred gatherings. Chants and slogans function as mantras. Activists rise as prophets. Public figures are canonized or anathematized. Identity accessories — masks, pins, pronouns — are the vestments of ideological belonging. Cancel culture serves as excommunication, drawing sharp lines of inclusion and exclusion. Each tribe has its dogma, its saints, its martyrs, its heresies. Argument yields to ritual. Reason yields to purification.

Nietzsche foresaw this transformation. In The Genealogy of Morals, he challenged the assumption that science could fill the void left by religion. Science, elevated into a worldview, becomes what he called “the latest and noblest form” of the ascetic ideal. Even the worship of truth is a metaphysical inheritance:

“We godless men and anti-metaphysicians… still derive our flame from the fire ignited by a faith millennia old, the Christian faith, which was also Plato’s: that God is truth, that truth is divine.”

(Genealogy III.24)

The outcome is not Enlightenment’s rational utopia, but a fragmented symbolic order ruled by resonance rather than reason. Visibility becomes the currency of meaning. Virality replaces truth. Ṭoḇ waRaʿ replaces Emeth weSheqer. The digital ecosystem rewards what is emotionally potent, not what is rationally coherent. The central question is no longer “Is it true?” but “Will it land?”

This symbolic disorder extends even to the body. Practices once associated with ascetic monasticism now unfold in digital forms. Public acts of self-abnegation — apologies, ideological disclaimers, moral self-policing — mirror religious flagellation. These are not enforced by state or clergy, but emerge from within, internalized as part of a shared moral imagination. Even irony and ambiguity are subject to theological scrutiny. Every utterance becomes a doctrinal risk.

Eschatological vision has also shifted. Movements surrounding climate change, racial justice, or technological disruption produce secular apocalypses and offer paths to redemption — not through divine grace, but through policy, protest, and purification. Atonement comes through lifestyle, linguistic discipline, and ideological fidelity. Salvation is behavioral.

What these modern faith-substitutes lack is not ritual or moral fervor, but roots. They have no canon, no prophets, no enduring texts. Their sacraments play out not only online but in the streets — through protests, tribunals, boycotts, and chants. They move with sacred intensity, yet mock the very traditions that taught the world how to sanctify. Myth, to them, is a lie we told ourselves to survive, not a structure we inherited to remember. They treat history as something to flatten, rewrite, or discard — a propaganda of the past to be torn down. But without myth, there is no memory. And without memory, no meaning.

This is why, in the midst of moral exhaustion, many are returning — not to trends, but to traditions. Structured Catholicism. Orthodox Christianity. Even Islam. These are not escapes from the modern world, but rebindings to something deeper. They offer what “wokeism” cannot: structure. Not performance, but formation. Not immediacy, but inheritance. Something older than the moment, and strong enough to survive it.

We have not transcended religion. We have transposed it. The hunger to believe, to belong, to be absolved and redeemed — these remain. What is lost is not faith, but the institutional forms that once gave faith structure. Nietzsche’s concern was not just the death of the Christian God, but the symbolic unraveling that followed:

“What did we do when we unchained this earth from its sun? Are we not plunging continually?”

The secular world is not secular. The sacred has not vanished. It has been redistributed. We inhabit a digital cathedral now — crowdsourced, psychologically totalizing, enforced by algorithm. It baptizes with hashtags, ordains through outrage, canonizes the trending. The forms remain. The sacraments continue.

The center is empty, yet the cathedral still stands.